Figures on a Cliff

The rock-pool is where my voice sounds best.

To one side of an empty strand, where a single

tent is pitched to add a point of colour

to the scene, the breeze is lightest,

and my voice sounds best. In the rock-pool,

half-hidden by boulders and an upturned boat,

I am testing the air. I sing what I see,

find notes for sand, the cliff, the hills across the bay.

The scene is set. An evening early in the year.

A woman stands alone on the beach

with her dress hitched up, and her hair undone,

making music with the rhythm of the sea.

What would it take to turn this scene around,

to render me irrelevant, a figure

almost covered in by stone, drawn against

an ocean that will surely take me in?

A woman and her song are details.

The figures on the cliff have barely noticed me.

A slight shift in perspective, and I disappear.

The cliff is more imposing, the sand attracts the eye.

The dull insistence of the sea absorbs it all.

There are darknesses to counter what I wear.

Even my silver bracelet can't outshine

the light that snags on shingle near the wall.

Where I stand is hardly worth a second look

unless the eye is caught by something else:

the play of light; a seagull on the wing;

my skirt, worried by a sudden wind that shows

my legs as quartz against a limestone drop;

a drift of song that's barely audible.

But I may stay. The light is kind.

I could take up my song where I left off.

The sun may be drawn back, and once more

I will stand as the centre of it all.

My song may outstay the waves, and my hands,

to give it strength, instruct the sea.

In time, the pool may draw the warmth from me

and the scene its point of reference, until

the light moves, just fractionally, away

to where the cliff figures, inscrutable, pristine,

are unaware of their importance,

are surprised at being seen.

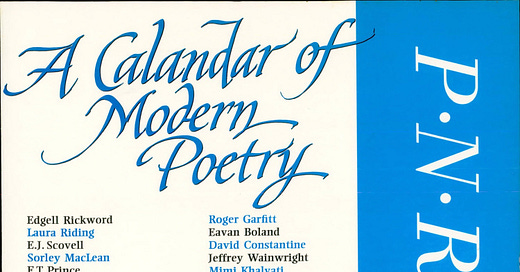

If you are engaged by what you read on our free Substack, do consider subscribing to the magazine. Like all independent literary magazines, PN Review relies on paid subscribers to survive. Subscribers have access to our entire fifty year archive, plus six new issues per year, in print and digital form.

A Tree Called the Balm of Gilead

What is it that is done

and undone in a name?

How is it that the Tacamahac

from North America has come

to rest on waste ground beside

my home, to be named in my book

of trees, the Balm of Gilead?

These poems by Vona Groarke are taken from PN Review 100, November - December 1994. Further contributions from Groarke, including the rest of the poems in this issue, are available in the archive to paying subscribers, as well as more poetry, features, reviews and reports from across the back catalogue.

If you are interested in the work that we publish on this Substack, subscribe to the Carcanet newsletter, where we share articles by our authors, translators and editors about upcoming books.