The Fourth Cambridge Conference of Contemporary Poetry

Fifty-five poets were included in The New Poetry, whose editors stress their 'total openness to what is being written' by English and Irish poets under fifty. Almost as many have performed at the Cambridge Conference since 1991, of whom forty-odd were eligible. Guess how many were chosen? Not that the conference, for its part, professes 'total openness to what is being written'. The sensible course might just be to accept things as they are: the Cambridge poets are thriving on the peripheries, and have been, in some cases, for thirty or more years. Some take evident pride in their status as 'hole-in-corner eccentrics and unsellables' (Peter Riley).

Such questionable 'status' is succinctly politicised by Drew Milne in the current issue of Parataxis, the journal of which he is now sole editor:

The danger is of developing hibernation strategies which envisage a future whose solace is retrospective… If the value of poetry is seen as dependent on posterity, and thus in opposition to strategies of intervention in the present… then contemporaneity is mortgaged to aesthetic ambition.

Milne identifies the true cost of neglect to poets and potential reader alike. At the conference, he saddled himself with a pointless slogan - 'The Death of Poetry' - and I found his 'speculative provocations' hard to square with his excellent analysis of 'Foot and Mouth', one of Prynne's most cuttingly ironic poems. It's certainly worth asking 'whether it is possible to maintain any conception of poetry… as a mode of cognitive or aesthetic truth'; but in rephrasing the question along lines suggested by Adorno, Milne proceeds to beg or at any rate to narrow it: 'In what sense can poetry articulate the divided linguistic labours and social antagonisms from which it works to free itself?' On the strength of 'evidence of unacknowledged accents of power in its presuppositions', poetry is condemned. So what price its 'contemporaneity'?

Parataxis has drawn inspiration from The English Intelligencer, a short-lived but brilliant organ to which Prynne contributed 'news items' later published as Kitchen Poems (Cape Goliard, 1968; the title a warning to those who can't stand the heat?) and table talk that would be worth reprinting in full, if Milne's citations are any sample:

sound in its due place is as much true as knowledge… Rhyme is the public truth of language, sound paced out in the shared places, the echoes are no-one's private property or achievement thus any grace (truly achieved) of sound is political, part of the world of motion and place in which language is like weather, the air we breathe.

Happily, the performers at the conference gave living confirmation of Prynne's words, which would bear rereading by Milne himself. I missed the session on Friday evening, and the Sunday afternoon and evening sessions, but all the performances I caught were memorable, in one way or another.

If you are engaged by what you read on our free Substack, do consider subscribing to the magazine. Like all independent literary magazines, PN Review relies on paid subscribers to survive. Subscribers have access to our entire fifty year archive, plus six new issues per year, in print and digital form.

The Black Country accent has become quite fashionable, though it still tends to be played for laughs. It was an unknown quantity to me, so I found it intriguing to listen to Roger Langley:

And, looking out, she might

have said, 'We could have all

of this', and would have meant

the serious ivy

on the thirteen trunks, the

ochre field behind, soothed

passage of the cars, slight

pressure of the sparrow's

chirps -just what the old glass

gently tested, bending,

she would have meant, and not

a dream ascending.

'Mariana' consists of eight twelve-line stanzas, its namesake of seven, Langley reimagines Mariana's erotic despair in a Midlands 'Sunday Morning' of 'certainties' and 'ordinary light', 'the consummation of the swallow's wings' rediscovered, with only a touch less afflatus, in 'the/quiet squall of martins'/wings again'. Stevens's sumptuous sub-Tennysonian poem also consists of eight (fifteen-line) stanzas, and Langley's cadences and line-breaks are played against iambic rhythms often as regular as Stevens's own: 'across the bevel/of the ceiling's beam, and,/shaken by the flare of/quiet wings…' Tennyson would surely have spotted the theft of 'The sparrow's chirrup on the roof (and the mirror-motif from 'The Lady of Shalott'); and, having thrown up his hands in horror at line-breaks after 'It' and 'the', would have applauded the lovely pun on 'chastened': 'It/chastened most of what the/sparrow said'. Langley's poem has its 'magic sights' and mythological tropes 'amorini'; 'sequins in the air' - but its absorption in 'just what the glass finds real/enough to bend' entails no loss of 'contemporaneity'. Twelve Poems (numerology again - of 'the serious ivy/on the thirteen trunks'), has just been published by infernal methods, reprinting the contents of Hem (1978) and Sidelong (1981). Though slimmer than most first collections, it actually amounts to a Collected Poems, and ought to establish Langley once and for all.

Pierre Alferi began by placing a French Oxo cube- 'KUB OR'- on the grand piano, an amusing reprise of 'Foot and Mouth', in which Prynne relishes his 'skilfully seasoned 10½oz. treat', a 'garishly French gold medal' winning can of 'Campbell's Cream of Tomato Soup'. KUB OR is a series of seven-line poem-cubes, whose elegant mordancy is typified by 'preface':

en voila une idée grunge

sept fois sept fois sept fois sept

et tirée par les cheveux

encubes durs d'à peu près

n'importe quoi tiens comme à

la télé presque aussi bonne

que de comprimerl'ordure

The poet read each cube in French and English, with its title(s) in between, like the answer to a riddle, though as often as not a sense of enigma remained. Some of the pieces are distinctly Symboliste - 'atterit sur/trains de latex rouge et sous/les roues saigne un sang de rat' ('pigeon') - but the beautiful plocaic opening of 'choriste' reminded me of 'Consolation à M. de Périer' by the even less grungey Malherbe (incidentally, I'm sure Spender was recalling 'Et rose elle a vécu ce qui vivent les roses' when he wrote 'Born of the sun they travelled a short while towards the sun'):

la première seconde elle

en rapelle une autre puis

elle-même à la seconde

KUB OR is forthcoming from P.O.L., and Sun and Moon are to publish two earlier collections in translation. With any luck British presses will follow suit, but I wouldn't wait, if I were you.

I was lucky enough to attend the world première of Something's Recrudescence Through To Its Effulgence (published by Equipage as Four Poems, 1993) in Michael Haslam's garden delph at Foster Clough, above the valley between Hebden Bridge and Mytholmroyd, a memory not eclipsed in the Keynes Hall. Still, I wouldn't have missed the repeat performance. The poetry has its heroicomical moments, but Haslam always gets away with it:

It's late at night. I stop and doff

my shoes and trousers, feeling soft

and pent in comfortable underpants.

Coleridgean archaisms, reminted in Marks and Spencers pentameters, intricate paranomastic rhetoric and unmistakable truth to experience are Haslam's rather exclusive stock-in-trade:

here you can smell the effluvial stream

from the mill, while the nightshift sweats

over cotton. The dusk falls through

the cliff of woods

to the fluminous swirling bend;

like a line sent on an errand

it will come back empty-handed in the

rain.

Like 'pent' and 'doff, 'fluminous' is more, not less, alive than its supporting cast of (more or less) 1990s idioms, focussing the 'f alliteration in a sense of twilit foaming that gives the Latin root a tangible presence. Industrial effluent is as intimately characteristic of Haslam's Pennine nocturne as Fisher's pollutants are of 'After Working', 'the petrol haze/that calms the elm-tops' and 'the dog odour/of water' (which I too associate with swifts). Haslam is as long-neglected and as fine a poet. His brilliant correction, in a letter to the LRB, of a learned authority on the Scapegoat may well have carried its subliminal point: 'Unless things have changed since I went to Sunday. school, the whole point about the Scapegoat is that it isn't sacrificed and it isn't killed: it is expelled… It's generally been easier for the figure expelled, one way or another, to return.'

Haslam's 'Belligerent Humility' was equally evident in his Parataxis review of David Marriott, as deep an engagement with a fellow-poet as I have read. As editor of folded sheets, he found in Marriott's early verse (circa 1986) an 'intuitive sense in thick poetic obscurity': 'I did not understand it; I liked it very much'. Exactly my own response, at the time, to 'Bauen: Wind':

Round eye, driven fossil, a riven ditch,

A walk, a cold tax; dog hedge. No hazel

Joy chaste at the given memory. No

replete

Wage or crossed wind. Waged god: wind,

Jihad

Clay, what outward glance, eye, & solar

Breath? We love the clean work; the

Occult breath, the shut elder wood. But

Who listens? The seed, now chalk, births

A little drum. Mark at glorious Wheel, &

Last nemesis, a scarlet cloud and reposed

Mansion: the wind beat, swift; cloudline

In bounded iron. Soft; & egre: men,

unfallen.

o ciborium/ebb.

And still. There is an indebtedness to Prynne, but Marriott's 'Occult breath' is as distinctive as it is disquieting. So it's sad to have to report that his talk and his performance were equally dire. Not content with mere tautology, Marriott has resuscitated a Coleridgean neologism, 'tautegorical', which enables him to construct sentences such as this one: 'The point is to address the tautegorica! imbrication of the philosophical and the theological thetic as symptom of the postmodern'. I wonder if this would cut any ice with Occam (on whom Marriott is an authority). The point about Marriott's 'interrogat(ion)' of the 'disremption between episteme and logos' as manifested in Olson's treatment of the word 'like' is not that it was incomprehensible, but that it was so clearly meant to be.

Haslam concludes his review of the recent work with an almost cruelly accurate comparison: Marriott as Malvolio. Neither out-of-synch hand movements nor squeaky shoes could detract from the poet's -and the poetry's - unfortunate arrogance. Lative (Equipage, 1992) is a remarkable book by a gifted poet; like Haslam, 'I admire David Marriott's work, but I do not choose to envy him his gift': 'What, given so much inner abuse, could I be but inaction,/a majestic reticence in face of the non-ordained?'

Fanny Howe struck me has having a particularly beautiful voice, but I've acquired a couple of her books and can confirm that her poetry has a voice of its own. Poem From A Single Pallet, with its marvellous illustrations by Colleen McCallion, was a snip at £5:

Time's flashy entity - What a swan!

The looped neck

has charmed us, afternoons of grey

ducklings…

Grey the bellsong curling over the sea -

grey

in the dust off Vineyard's grey point…

The Line is out, looped through

the mature lines of noon - the Score: a

langorous

Reality, sooner doubted than true

The lovely final cadence and internal rhyme of those opening lines, and their synthesis of abstraction and sentiment, are mirrored in the close:

I understand my fears, in sunlight,

a day's work,

pursued by the invisible spirit of

Childhood, where some say

pain is Evil, some say Good

There is something of Emily Dickinson in the New England air of her poetry, 'snow-lit like/the house of suffering/known by no-one but who's in'; 'aloof/like Mayhem from the bourgeois life' yet finding in 'prim Thimble Islands,/work without relief' a solacing thought. Fanny Howe is a contributor, alongside her sister, Susan Howe, to In the American Tree (NPF, 1986). This magnificent anthology of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry has yet to be assimilated in Britain, but the Supreme Soviet of CCCP is beginning to put things right.

For the rest, Peter Hughes, Grace Lake, Helen MacDonald, lain Sinclair and the duet of Out to Lunch and Simon Fell all gave excellent performances, and rather than slight them with short shrift, I'd prefer to keep my powder dry and write about them on another occasion. I was particularly sorry to have missed David Chaloner, whom I've never heard, and Peter Riley, whom I've heard several times (no disrespect to Derek Bailey on guitar, Olivier Cadiot, Jaques Roubaud or Barbara Guest). In conclusion, a request: any chance of a Longville gig at CCCP5?

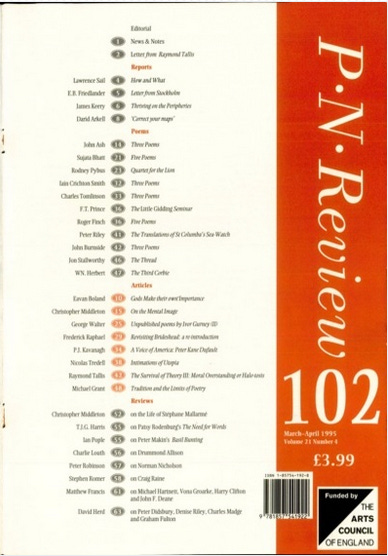

This report is taken from PN Review 102, March - April 1995. James Keery edited edited Carcanet's anthology Apocalypse and the forthcoming Conjurors: Poems by Julian Orde. Keery’s many contributions to the magazine are available to paying subscribers.