Quartet

Ore, fermate il volo

e, carolando intorno

a l'alba mattutina

ch'esce de la marina,

l'umana vita ritardate e'l giorno.

– Tasso

I.

KNOWN yet always strange, the lie of the land,

the riddle of the palm of one's own hand.

The ocean sculpts in each wave, stubbornly,

the monument in which it falls away.

Against the sea, a will that's turned to rock,

the faceless headland keeps the sea in check.

The clouds: they are inventing sudden bays

– where a plane is a barque that melts away.

The rapid scribbling of the birds above

– others are fishing where the water moves.

Between the sea-foam and the sand I tread,

the sun is resting light upon my head:

between what's static and what will not stay

in me the elements enact their play.

II.

THERE are tourists also on this strand,

death in a bikini, death with jewelled hand,

there are rumps and bellies, loins, lungs, thighs,

a cornucopia of bland enormities,

a scattered abundance that precedes

the meal of ashes where the worm will feed.

Adjacent, yet divided by those lines

strictly kept but tacit, undefined,

are vendors, and the stalls where fries are sold,

and panders, parasites, untouchables,

the rags of poor men and the poor man's bones.

The rich are stingy while the poor man fawns:

God loves them not, nor do they love themselves:

'each does but hate his neighbour as himself'.*

III.

The wind breaks forth and gathers up the grove,

the nations of cloud disperse above.

The real is fragile, wavering, unsure

– also, its law is change, it does not tire.

Round and round the wheel of seemings spins

upon a fixity: the axis time.

Light sketches all and then turns all to flame,

with daggers that are brands it stabs the main

and makes the world a pyre of mirrorings:

we are mere white horses of the sea.

It's not Plotinus's light, it's earthly light,

a light of here, but it is thoughtful light.

It brings, between me and my exile, peace:

my home this light, its shifting emptiness.

IV.

TO wait for nightfall, I have stretched myself

under the shadow of a throbbing tree.

The tree is a woman in whose leaves

I hear the ocean roll beneath noon heat.

I eat her fruits that have the taste of time,

fruits of forgetfulness, fruits of wisdom.

Beneath the tree, the images and thoughts

and words regard each other, touch.

Through the body we return where we began,

spiral of stillness and of motion.

To taste, to know – it is finite, this pause:

it has beginning, end – is measureless.

Night enters and it rolls us in its wake;

the sea repeats its syllables, now black.

Translated by M. Schmidt

*Alexander Pope

Two Texts

(Charles Tomlinson translates two inédits by Octavio Paz, one in verse and one in prose, to be added to the American edition of El Mono Gramatico which will appear in 1981.)

I open the window

that gives

onto nowhere

The window

that opens inwards

The wind

raises

instantaneous weightless

towers of whirling dust

They are

higher than this house

They fall

onto this page

Fall and rise again

Before they say

something

at the turning of the page

they scatter

Whirlwinds of echoes

aspired inspired

through their own gyration

Now

they open into another space

They say

not that which we said

another thing always another

the same thing always

Words of the poem

we never say them

The poem says us

A work of art never possesses a real reality. While I am writing, there is a point beyond writing which draws me on and which, each time I seem to have reached it, eludes me. The work isn't that which I am writing, but what I do not finish writing – that which I do not get to write. If I stop and read what I have written, the gap appears once more: beneath what is said there remains the unsaid. Writing rests on an absence, words cover up a hole. In one way and another, a work of art suffers from unreality. All works, not excluding the most perfect, are the presentiment or the rough draft of another, the real one, which never gets written.

The solidity of a work is its form. The echoes and correspondences between the elements which compose it, set up a visible coherence which unfolds before our eyes and mind as a whole: a presence. But the form is constructed above an abyss. The unsaid is the fabric of speech. Form is an architecture of words which, reflected in one another, reveal the underside of language: the not-meaning. A work does not say what it says, but says what it doesn't say. It says this independently of what the author wished to say and of what itself, in appearance, is saying. A work does not say what it says: it always says something else. The same thing.

A work of art is unusual because the coherence which is its form reveals to us its incoherence: that of our own selves which we say without saying and thus say ourselves. I am the blank space of that which I say, the white paper of that which I write. Form is a mask which does not hide but reveals. But what it reveals is a question, a not-saying: a pair of eyes which look down on the text – a reader. Through the mask of form the reader discovers not the author but, in his reading eyes, the unwritten in the written.

The poet is the reader of himself: the reader who discovers in what he writes, while he writes, the presence of the unsaid, the absence of saying which is to say all. The work is the form, the transparency of language over which there appears – untouchable, illegible – a shadow: the unsaid. I likewise suffer from unreality.

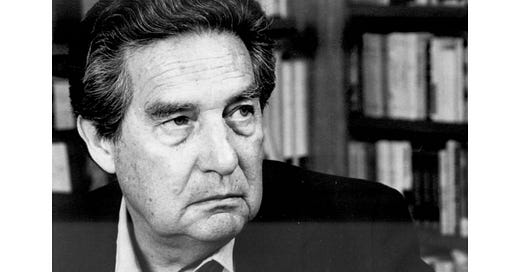

Octavio Paz (1914–1998) was a prolific Mexican poet and essayist. He studied at the University of California at Berkeley for two years before entering the Mexican diplomatic service, from which he resigned in protest against his government’s massacre of student demonstrators before the Olympic Games in 1968. His postings took him to Paris – where he wrote The Labyrinth of Solitude – India, Tokyo and Geneva. He was awarded the 1990 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Charles Tomlinson (1927-2015) studied at Queens’ College, Cambridge. He published many books of poetry, and translated selections from Russian, Spanish and Italian. He was also an artist. He taught at Bristol University, where he was appointed Emeritus Professor of English Poetry.

Michael Schmidt FRSL, poet, scholar, critic and translator, was born in Mexico in 1947; he studied at Harvard and at Wadham College, Oxford, before settling in England. Among his many publications are several collections of poems and a novel, The Colonist (1981), about a boy’s childhood in Mexico. He is general editor of PN Review and founder as well as managing director of Carcanet Press.

Subscribe to PN Review magazine at pnreview.co.uk.